Christine Braid, Massey University

Meet Otis. He’s eight years old and until recently he didn’t want to read or write. Then his teacher changed the way she taught and things began to improve.

After a few weeks, Otis (not his real name, but he’s a real child) wanted to read and write at every opportunity. With this new-found knowledge and motivation his skill increased too. And his confidence.

So what was different? Technically, Otis’s teacher had begun using what is known as a structured approach to teaching literacy. Essential for children with a literacy learning difficulty such as dyslexia, it has been shown to be beneficial for all children.

The structured approach is a departure from what is known as the “implicit” teaching approach most teachers have used in the classroom. There are now calls for “explicit” instruction to be adopted more generally, including a petition recently presented to the New Zealand Parliament.

New data suggest this is an urgent problem, with growing numbers of young people turning off reading. According to a recent report from the Education Ministry’s chief education science adviser, 52% of 15-year-olds now say they read only if they have to – up from 38% in 2009.

The report made a number of recommendations, including that the ability to “decode” words become a focus in the first years of school. The importance of decoding to literacy success was reiterated by learning disability and dyslexia advocacy group SPELD NZ. It called for a change in teacher training and urgent professional development in structured literacy teaching.

Read more:

Why every child needs explicit phonics instruction to learn to read

How does a structured approach work?

Structured literacy teaching means the knowledge and skills for reading and writing are explicitly taught in a sequence, from simple to more complex. Children learn to decode simple words such as tap, hit, red and fun before they read words with more complex spelling patterns such as down, found or walked.

Learning correct letter formation is a priority. Mastery of these skills builds a strong foundation for reading and writing, without which progress is slow, motivation stalls and achievement suffers.

Author provided

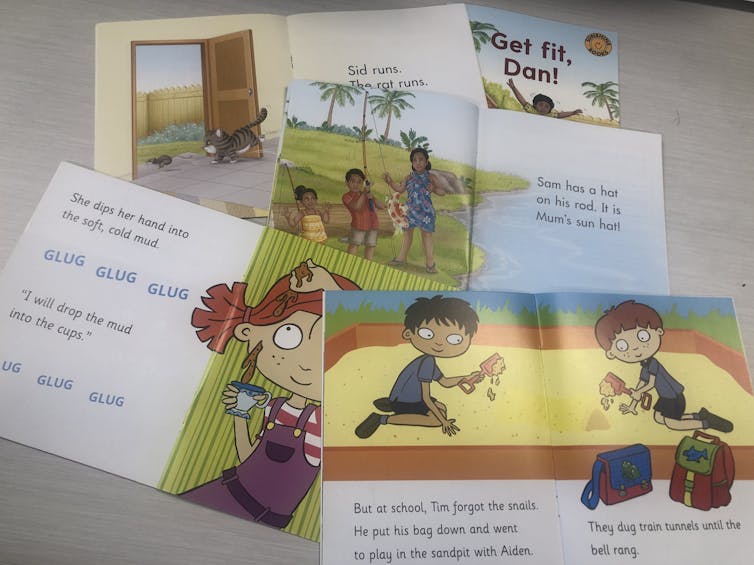

The books children first read in a structured approach employ these restricted spelling patterns. Reading these with his teacher’s help, Otis built on his skills with simple words and progressed to decoding words with advanced spelling patterns.

These structured lessons also allowed him to master letter and sentence formation, so he made progress in writing too.

Old approaches aren’t working

By contrast, an implicit approach to teaching reading essentially means children have lots of opportunities to read and write, and learn along the way with teacher guidance.

Unfortunately, children like Otis can get lost along the way, too.

Implicit reading books use words with a variety of spelling patterns – for example: Mum found a sandal. “Look at the sandal,” said Mum.

When Otis tried to read these books, he looked at the pictures or tried to remember the teacher’s introduction before attempting the words. But he was not building his skills and was getting left behind.

Otis is not alone, and New Zealand’s literacy results support the calls for change. Despite many interventions and the daily hard work of teachers, it is common for schools to report 30% of children with low reading results and 40% with low writing results.

However, a Massey University study in 2019 found reading outcomes improved when teachers were trained in a structured approach. The results were particularly good for children with the lowest results prior to intervention.

Overall, the findings suggest the change in teaching had a positive effect on children’s learning.

Change is already happening

Fortunately for children like Otis, more teachers are now seeking training in a structured approach. One project based on the Massey research involved more than 100 teachers in over 40 schools. Teacher comments suggest the knowledge and training support has helped them change their teaching for the benefit of the whole class.

Further signs of hope include recent Ministry of Education efforts to develop structured approach teaching materials, and the resources now available for teachers on the ministry’s Te Kete Ipurangi support site.

No one pretends change is easy in a complex area such as literacy teaching. But every child like Otis has the right succeed, and every teacher has the right to be supported in their approach to helping Otis and his peers learn.

With courage and effort at every level of the system – not just from classroom teachers – a structured approach to literacy teaching can improve outcomes and have a positive impact that will stay with children for the rest of their lives.![]()

Christine Braid, Professional Learning and Development Facilitator in Literacy Education, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.