Us readers know how awesome we are. And if we ever socially interacted with people everyone would realise that. We also want to know that we’re not alone. In a holistic sense. Obviously alone in the physical sense because otherwise, someone would try to interrupt our reading.

Sensing our need for connection to a nationwide community of book nerds, The Australian Arts Council commissioned a report to figure out who was reading books. The report surveyed 2,944 people to see who read, how much, how they found books, and whether they preferred waiting for the movie adaptation. Let’s see what they found.

Firstly they wanted to establish how often people read and how that compared to other leisure activities. Reading was obviously less popular than dicking around on the internet and watching TV, but apparently beat out exercise. Although they excluded sport, and Aussies have a funny definition of sport. But this finding is similar to 2006 ABS figures that suggest Aussies spend 23 minutes per day reading, versus 21 minutes for sport and outdoor activities, and 138 minutes for Audio/Visual Media (Table 3.3).

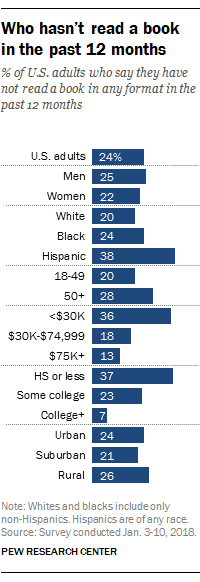

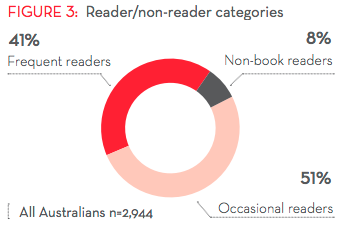

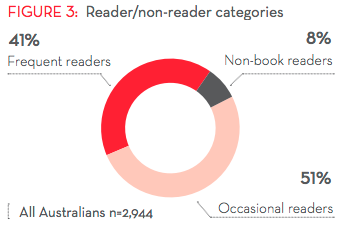

Next are the reader categories. Non-readers were actually a small group, mostly male and more likely to have less education (although I wouldn’t read too much into that last detail). Occasional readers made up half the population and were defined as reading 1 to 10 books in the last 12 months. Frequent readers were a surprisingly large segment, were defined as reading more than 10 books in a year, and were mostly female, older, better educated, and clearly better looking with tonnes of charisma.

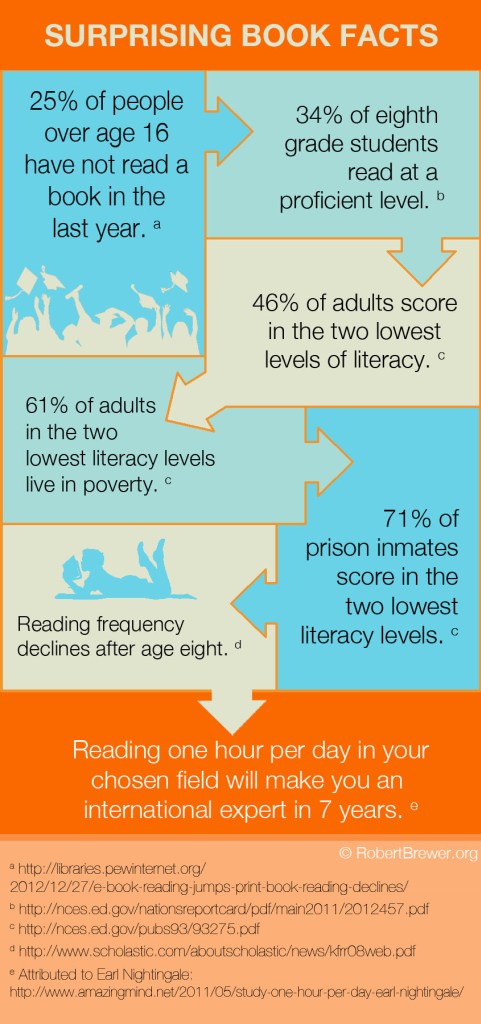

Reading is to intellectuals what the bench press is to lifters. On the surface, they might appear to be a good representation, but most exaggerate how much to appear better than they really are. Oh, and they generally aren’t fooling anyone… So I’m a little suspicious of the popularity of reading suggested by the above figures.

For one, only 34% of Aussies have visited a library in the last 12 months (2009-2010 ABS data) and 70% of them attended at least 5 times. Yet this new survey suggests 39% of people borrowed one or more books from a library in the last month. That’s roughly comparative figures of 24% from the ABS and 39% from this survey.

I’m suspicious. This survey might not be as representative as claimed. Or reading may have suddenly risen in popularity since 2010… Doubtful given that both the ABS and this survey suggest otherwise. ABS suggested the amount of time spent reading had decreased by 2 hours between 1997 and 2006, whilst this survey suggested the book reading times were roughly the same as 5 years ago (Figure 8 – not presented).

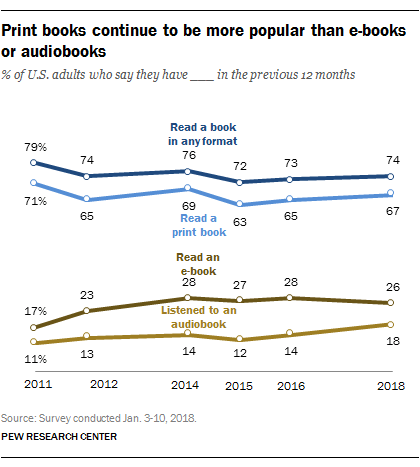

The next figure of average reading rates either suggests Aussies are reading quite a bit, or inflating their numbers like an “all you” bench press. The average Aussie is reading 7 hours a week (5 of those for pleasure) and getting through 3 books a month (36 a year: not bad). Occasional readers are reading one book a month from 5 hours a week, compared to the Frequent readers who are reading 6 books a month from 11 hours per week (72 books a year: nice).

But I’m not sure how accurate these claims are. I cited ABS figures above that suggested Aussies spend 23 minutes per day reading, or 2hrs 41mins (161 minutes) per week. So either one of these two samples is unrepresentative, or some people just love to inflate how much they read. I’m leaning toward the latter.* But you can trust me on my bench press numbers. Totally accurate and “all me”.

The final figure I found interesting was of favourite reading genre. When you included non-fiction and fiction genres there were two clear winners: Crime/Mystery/Thrillers; and Science Fiction/Fantasy.

These are our favourites yet our bookstores would suggest that Sci-fi and Fantasy are niche and only deserving of a shelf at the back of the store. Cookbooks, memoirs, literature, and the latest contemporary thing that isn’t quite literature but isn’t exciting enough to be genre, are typically dominating shelves in stores. This would annoy me more if I wasn’t already suspicious of how representative this survey was, or how honest the respondents were being.

It could well be that people enjoy reading Thrillers and Fantasy but feel compelled to read other things. Maybe people are brow-beaten by the literary snobs to read only the worthy stuff and not the guilty pleasures. Maybe the snobs in Fort Literature have successfully turned favour against the invading Lesser Works. This might not be the case though, as 51% in this survey say they are interested in literary fiction but only 15% actually read it.

It could be that people are borrowing books from libraries or friends. Borrowing books is popular with 41% borrowing one or more books per month, mostly from friends (43%) and libraries (39%). But 39.5% bought at least one book in the last month (92% of 43% buying for themselves). So the tiny niche sections in bookstores for the most enjoyed genres still doesn’t make much sense.

I’m not sure what to make of all this. I mean, aside from Yay, Reading!

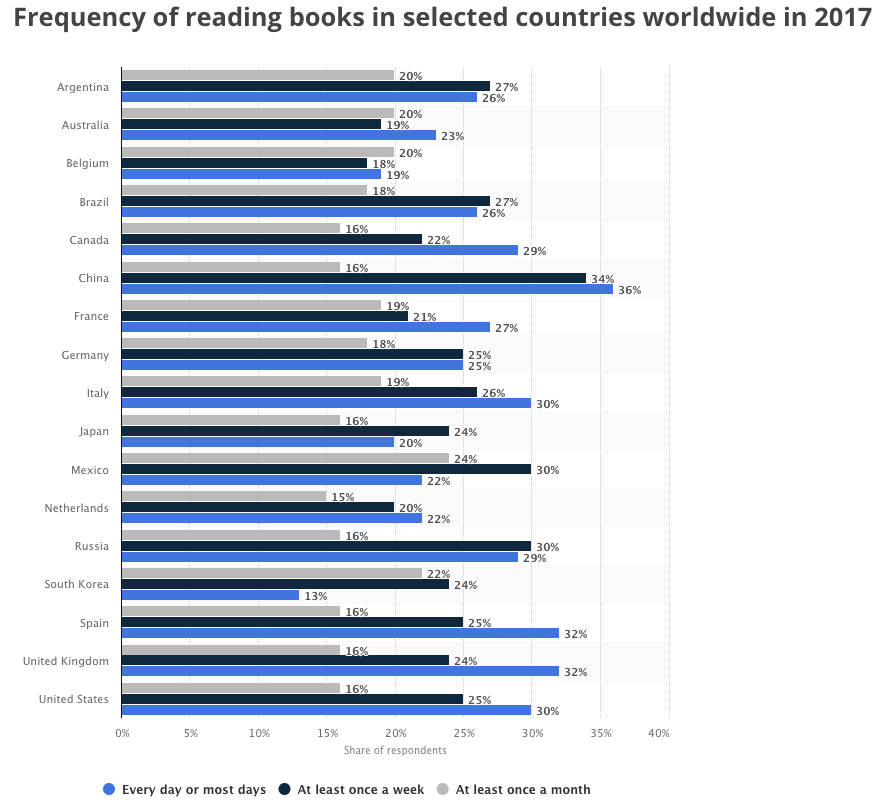

For comparison, the USA Pew Research’s 2016 annual survey of readers data is presented below. This suggests that Aussies read more than Americans. Assuming people are being honest.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

“Key” insights from the Aussie research:

• We value and enjoy reading and would like to do it more – 95% of Australians enjoy reading books for pleasure or interest; 68% would like to read more, with relaxation and stress release the most common reason for reading; and almost three-quarters believe books make a contribution to their life that goes beyond their cost. Over 80% of Australians with children encourage them to read.

• Most of us still turn pages but many are swiping too – While print books still dominate our reading, over half of all readers in-clude e-books in the mix, and 12% audio books. Most Australians (71%) continue to buy books from bricks-and-mortar shops, while half (52%) are purchasing online. Word of mouth recommendations and browsing in a bricks and mortar bookshop are our preferred ways to find out what to read next. At the same time, nearly a third of us interact with books and reading through social media and online platforms.

• We are reading more than book sales data alone suggests – each month almost as many people borrow books (41%) as those who buy them (43%) and second-hand outlets are the third most popular source for buying books (39%), after major book chains (47%) and overseas websites (40%). Those who borrow books acquire them almost as frequently from public libraries as they do by sharing among friends.

• We value Australian stories and our book industry – 71% believe it is important for Australia children to read books set in Australia and written by Australian authors; and 60% believe it is important that books written by Australian authors be published in Australia. While there is a common perception among Australians that books are too expensive, more than half believe Australian literary fiction is important. Almost two-thirds of Australians believe books by Indigenous Australian writers are important for Australian culture.

• We like mysteries and thrillers best – the crime/mystery/thriller genre is the most widely read and takes top spot as our favourite reading category. We also love an autobiography, biography or memoir. (Source)

* I’m biased toward the ABS survey results over the Australian Arts Council for a few reasons. The first is that the ABS data is part of a larger Time Use Survey (How Australians Use Their Time, 2006, cat. no. 4153.0), so this removes a few biases in how people would answer questions (i.e. ask people specifically about how awesome books are, you’re going to talk up your reading more). It is also the larger survey covering 3,900 households. The methodology was also more likely to produce better data since respondents were filling in a daily diary and being interviewed. The Arts Council methodology wasn’t bad, but the survey was developed by interest groups, so the questions were presuming some things.