Recently on the den of inequity and monetised dumpster fires, I posted a tweet.

This idea of how the “big brains” in Silicon Valley seem to miss the point of most speculative fiction has been in my thoughts lately. I’ve lost count of the number of articles I’ve read that have sung the praises of a new tech idea that was clearly ripped straight out of a dystopic novel.

Surely it isn’t just me and every other book nerd who understands that your favourite sci-fi novel was meant to be a warning, not a goal, right?

Well, this video from Wisecrack certainly appears to be on my side.

I think it is clear why tech-bros get sci-fi (and other spec-fic) wrong. The shallow, selfish and egotistical nature of being a Silicon Valley wonk precludes you from fully understanding subtle messages in fiction. You know, subtle messages like AIs will destroy the planet, anarcho-capitalism will destroy the planet, rich/greedy people will destroy the planet, pollution will destroy the planet, etc.

Take Musk’s Neuralink. When it’s not being inhumanely tested on monkeys, there is a lot of buzz around what it could do. Like brain uploading to make you immortal. Like in that sci-fi novel where people became immortal thanks to brain uploading. Which was a novel about how brain uploading was really really bad.

But is that the message that someone like Musk would take away from Altered Carbon? Would he look at that sci-fi dystopia and think “wow, bad, let’s not make brain uploading a thing” or does he look at it and think “wow, that rich guy had a sky palace and got to be super-duper immortal rich, let’s make that brain uploading a thing”? Hint, it’s the last one. Because that novel isn’t a dystopia for someone like Musk, it’s a utopia.

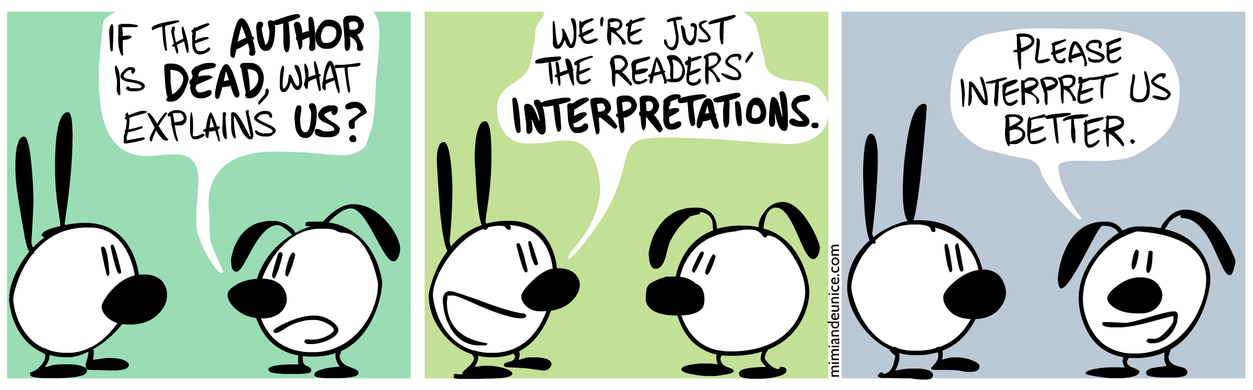

This is ultimately the point of speculative fiction. It makes comments upon our current society through fictional worlds, to show us the follies of our ways. The trick is to make sure WE heed the message and stop the rich and powerful from steering us (further) into dystopia.