I’m just going to say it: I’m comfortable with the label of nerd.

More specifically, I’m a Nerdius scientifica.

Being a nerd is more accepted nowadays, what with our bulging brains and chiselled knowledge. And the reality is that us nerds have a lot to offer, like research skills.

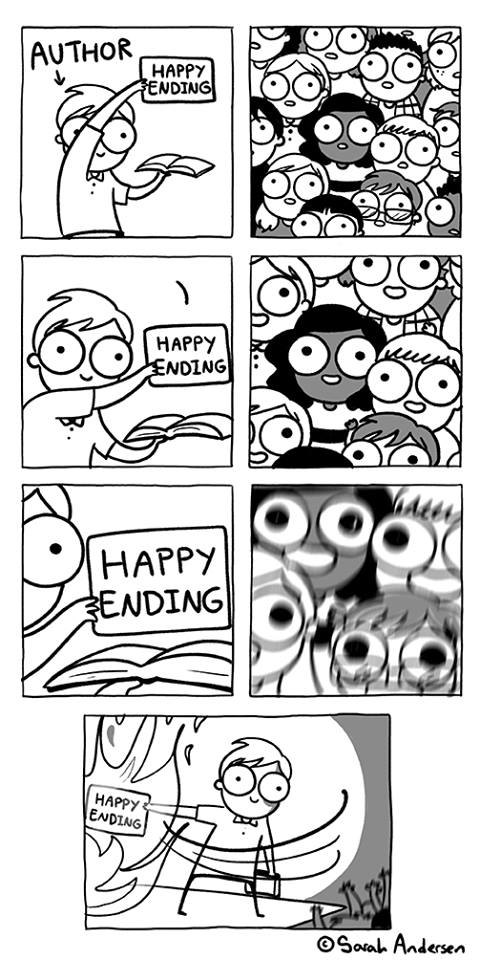

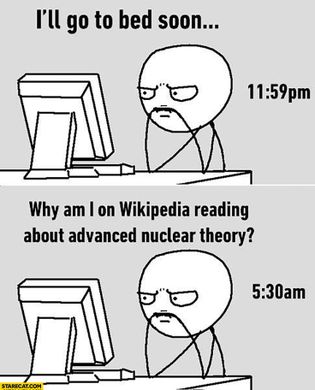

Writing requires a lot of research and writers generally fall into two categories in this regard: those who need to learn how to research, and those who took up writing to justify those dodgy topics they’ve researched. This post will hopefully help the former. But if anyone does want to know how much slack rope you need to hang someone correctly from your homemade gallows, I have a spreadsheet calculator for you.

I stole am reblogging a post from Writer’s Digest with a few of my own comments.

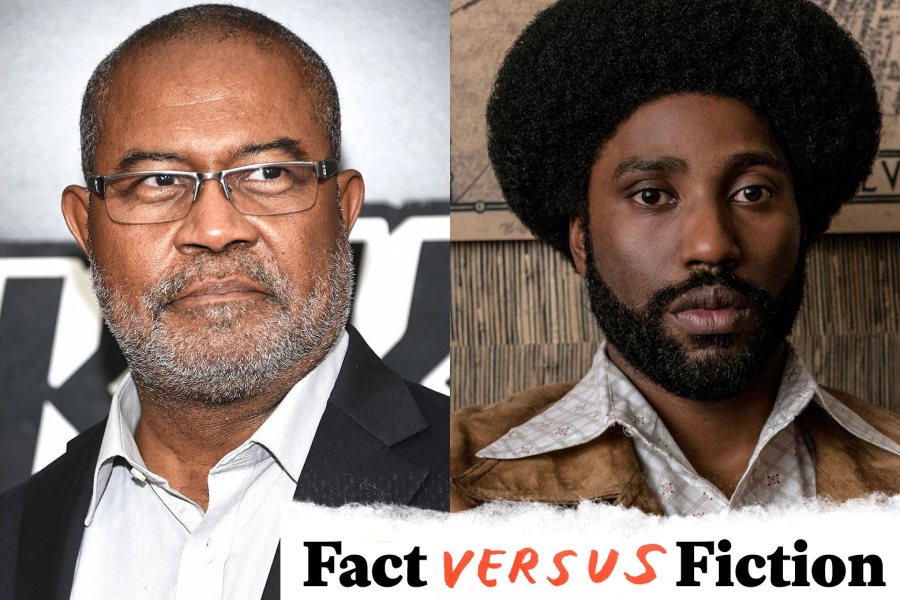

Ernest Hemingway said writers should develop a built-in bullshit detector. I imagine one reason he said that is because readers have their own BS indicators. They can tell when we writers are winging it. We have to know well the worlds in which our characters act. Readers don’t have to believe the story really happened, but they need to believe it could have happened. So with that in mind, I offer a few thoughts on research for fiction.

I’d argue everyone should have a BS detector. [Insert topical political joke here] But the important point to note is that a writer can’t be an expert in all topics, yet readers are likely to come from a wide background. So if you haven’t done your research thoroughly, readers who are well versed in a field will notice, which can ruin the book for them.

1) You can’t do too much research. In the military, we often say time spent gathering intelligence is seldom wasted. The same concept applies in writing a novel. You never know what little detail will give a scene the ring of authenticity. In a college creative writing class, I wrote about how a scuba diver got cut underwater, and in the filtered light at depth, the blood appeared green. Though the professor didn’t think much of that particular story, he did concede he liked that detail. In fact, he said, “The author must have seen that.” And indeed, I had.

This point is both true and false.

Gee, thanks Tyson.

You’re welcome!

Okay, what I mean is that while you need to have done enough research to be able to include those little details that sell the story, at some point, you have to stop researching and write the damn thing. Maybe you want to be able to accurately describe what arterial spray looks like for your serial killer novel, but you can only research that for so long before you need to put down the knife and pick up your pen.

2) You can write what you know. We’ve all heard it before. Experience may be a cruel teacher, but it is a thorough one, and experience is the purest form of research. Things you’ve done in life can inform your writing in surprising ways, even if your characters aren’t doing those same things. When I watch the old Star Trek shows, I can tell the creator of those stories knew something about how a military flight crew works together. He understood the dynamics of a chain of command, how a commander learns the strengths and weaknesses of his team, how those team members communicate and work together. Turns out that Gene Roddenberry flew B-17 bombers in World War II. Roddenberry, of course, never flew a starship. But he knew from experience how the crew of a starship might interact.

Soooo, about that serial killer novel… Pure research. No experience. I promise.

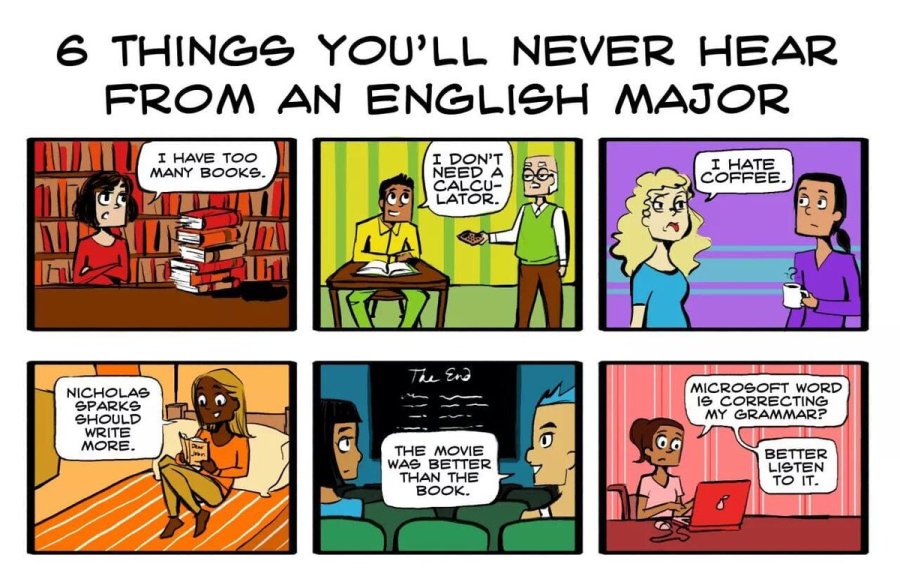

Writing what you know is one of those bits of advice authors receive that you can honestly shrug your shoulders at. It’s not untrue. If you’ve been involved in something as a professional you will know it better than anyone trying to research it. But it can also be severely limiting.

Take the example used. If Star Trek understands how military flight crews operated, why did it insist on sending the most important crew members on the dangerous away missions? Aside from the chance to shag the aliens, obviously.

I think the more helpful advice is seeking help from people who know. Go to forums, discussion groups, ask friends, put out the call on social media, cultivate contacts. The internet makes us closer than ever to experts, why limit yourself to what you’ve done?

3) You can do research on the cheap. If you can’t visit an exotic location, you can pick up the phone and ask questions. The worst that can happen is somebody thinks you’re crazy and they hang up. Then you just call somebody else. (Believe me; I used to be a reporter, and I’ve learned a lot by asking questions.) You can visit a museum, or a museum’s website. Develop an eye for small details.

While you CAN do research on the cheap you COULD still use your writing as an excuse for that holiday to an exotic location.* For your art. And tax write-offs.

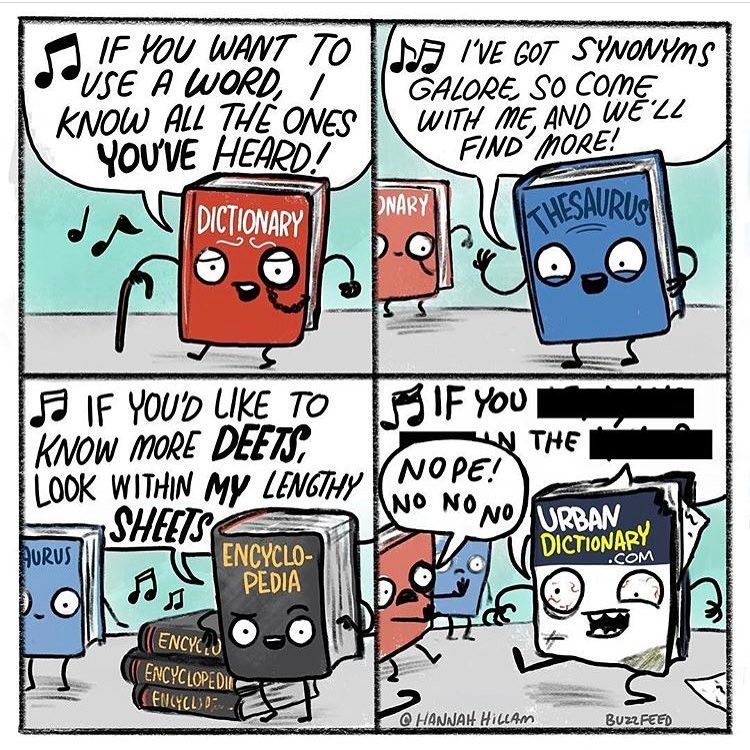

The internet is the cheapest and best research tool ever invented. Things like Google Street View, location webpages, travel blogs, and that person you went to high school with who fancies themselves as an Influencer’s Instagram feed, all offer information from your desk. No travel required. The same applies to any other aspect of research.

But be careful. Your Influencer friend might be distorting the truth for clicks. That travel blog may have been paid content from a tourism company. And Google Street View may be tracking your data to target you with ads.** Lateral reading and critical research are key.

4) You can find anything on YouTube. Seriously. But you have to know your topic well enough to know how to search for it. In The Renegades, I have a character whose lungs collapse from a bullet wound. I wanted to find out how a medic would treat that condition. Sure enough, someone had posted on YouTube a video with detailed instructions on how to perform a needle decompression.

You can find anything on YouTube. If you want to know about how the Earth is actually hollow and filled with shape-shifting lizards who have roles in every government and are most celebrities, then YouTube has you covered. If you want to know how vaccines are a secret government conspiracy by the lizard people to depopulate the planet and make the survivors docile sheep ready for the coming invasion, then YouTube has you covered. If you want to know how white people are being replaced as part of a globalist agenda and the only way to stop it is by becoming a Nazi, then YouTube has you covered.***

Again, lateral reading and critical research are key.

5) You can find things anywhere. You’re a writer, so keep pen and paper within reach during all waking hours. You might get an idea from a news story on television, a song on the radio, or a Tweet from a friend. About a year ago, I was driving along on a warm day, listening to the radio with the windows down. An oldies station played “Wind of Change,” the Scorpions’ 1990 ballad hailing the end of the Cold War. I hadn’t heard that song in a long time, and I cranked it up loud. The power chords brought back memories of flying relief missions to Bosnia while based at a disused Cold War alert facility in Germany. Not really a pleasant memory–for Bosnia, the end of the Cold War brought something worse. But that flashback from early in my military career inspired a scene in the novel I’m working on now.

While I agree with this point, I think people get carried away with always having a pen and paper handy. A lot of the ideas you end up writing down are rubbish. The flight of fancy comes and goes. The things you write down should be the sticky things. That thing you wanted to look up, you’ll remember it if it was actually important.

6) You can use all of your senses. Find out what things taste like, smell like, feel like. Say, for example, you set your novel in Warsaw. Maybe you can’t afford to go to Warsaw, but you can go to a Polish restaurant. (See item number three above, about doing research on the cheap.) As you write one of your scenes, include a line about the texture and flavor of something your character eats. You’ve just made your writing more alive and authentic.

This is good advice, particularly with internet research. It is easy to look up photos of a location. Harder to look up what it smells like, or if the road is uneven underfoot, or if arterial blood feels warm on your skin. We’ve got roughly 20 senses, so your research (and writing descriptions) should reflect that.

7) You can leave some things out. If you do thorough research, you’ll find more material than you need, and no reader likes a data dump. In my own writing, I could bore you to death with the details of aircraft and weapons. But a very good creative writing professor once advised me to let the reader “overhear” the tech talk. Say, if my character punches off a HARM missile, that might sound authentic and pretty scary. But scary would turn to dull if I stopped the action to tell you that HARM stands for High-Speed Anti-Radiation Missile, which homes in on anti-aircraft missile radars. Who cares? The damn thing goes boom.

This is the most important point about research, even in science. Most of it doesn’t end up on the page. Nobody cares about the lab experiments that failed, they want to know about the results from the one that worked. Nobody wants to read your detailed and accurate Linux commands the hacker types in, sudo leave that stuff out.

I think the point of research is to better understand the universe we live in. For a writer, research will help to create more believable universes for their stories. It isn’t easy to tell the difference between good and bad information. It isn’t easy to know when to stop. And it is hardest of all to not brag about how big your research is.

* Ever notice that novels by successful authors are never set in boring locations? The characters are never having the exciting chase scene through the streets of Canberra, Adelaide, or Perth Australia, they are in Paris, or New York, or London. Funny how those places are regarded as top destinations for travel.

** Maybe? Try definitely. I said may because you can run tracking and ad blockers and deny cookies. Good advice to stop some… interesting ads coming your way.

*** I’m not even covering the worst and most obviously wrong conspiracies with these examples. Not even close. Two of those three examples are getting people killed.