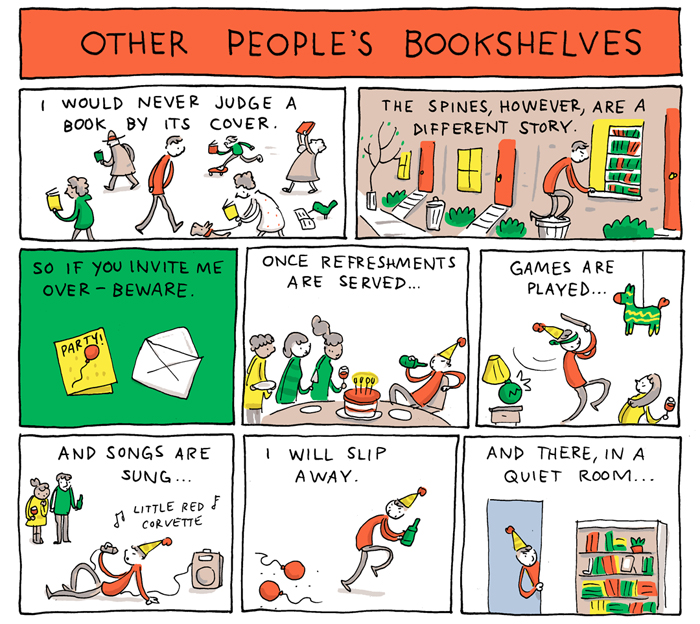

This comic from Nateswinehart captured my attention today. It was too good not to share. Visit his Tumblr to see more great stuff.

Category: Reblogged

Rebecca Giblin, Monash University

Last Tuesday Bryan Adams entered the copyright debate.

That’s Bryan Adams the singer and songwriter, the composer of “(Everything I Do) I Do It for You”, and “Summer of ’69”.

Authors, artists and composers often have little bargaining power, and are often pressured to sign away their rights to their publisher for life.

Adams appeared before a Canadian House of Commons committee to argue they should be entitled to reclaim ownership of their creations 25 years after they sign them away.

No control until after you are dead

In Canada, they get them back 25 years after they are dead when the rights automatically revert to their estate. In Australia, our law used to do the same, but we removed the provision in 1968. In our law, authors are never given back what they give away.

Some publishers voluntarily put such clauses in their contracts, but that is something they choose to do, rather than something the law mandates.

Australia’s copyright term is long. For written works it lasts for 70 years after the death of the author. It was extended from 50 years after death as part of the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement.

What copyright is for

Copyright is a government-granted limited monopoly to control certain uses of an author’s work.

It is meant to achieve three main things: incentivise the creation of works, reward authors, and benefit society through access to knowledge and culture.

Incentive and reward are not the same thing.

The incentive needn’t be big

The copyright term needed to provide an incentive to create something is pretty short.

The Productivity Commission has estimated the average commercial life of a piece of music, for example is two to five years. Most pieces of visual art yield commercial income for just two years, with distribution highly skewed toward the small number with a longer life. The average commercial life of a film is three to six years. For books, it is typically 1.4 to five years; 90% of books are out of print after two years.

It is well accepted by economists that a term of about 25 years is the maximum needed to incentivise the creation of works.

But the rewards, for creators, should be

The second purpose is to provide a reward to authors, beyond the bare minimum incentive needed to create something. Quite reasonably, we want to give them a bit extra as thanks for their work.

But, in practice authors, artists and composers are often obliged to transfer all or most of their rights to corporate investors such as record labels or book publishers in order to receive anything at all.

In the film and television industries it is not unusual for creators to have to sign over their whole copyright, forever – and not just here on Earth but throughout the universe at large.

Read more:

Life plus 70: who really benefits from copyright’s long life?

It means investors don’t just take what is needed to incentivise their work but most of the rewards meant for the author as well.

This isn’t new. Creators have been complaining since at least 1737 that too often they have no choice but to transfer their rights before anyone knows what they are worth.

Other countries do it better

In recognition of these realities, many countries, including the US, have enacted author-protective laws that, for example, let creators reclaim their rights back after a certain amount of time, or after publishers stop exploiting them, or after royalties stop flowing. Other laws guarantee creators “fair” or “reasonable” payment.

Australia stands out for having no author protections at all.

Read more:

Australian copyright laws have questionable benefits

Canada’s law already protects authors by giving rights back to their heirs 25 years after they die. Bryan Adams’s proposal is to change one word in that law. Instead of copyright reverting to the creator 25 years after “death”, he wants it to revert 25 years after “transfer”.

Copyright is meant to be about ensuring access

Handing rights back to creators after 25 years would not only help them secure more of copyright’s rewards, it would also help achieve copyright’s other major aim: to promote widespread access to knowledge and culture.

Right now our law isn’t doing a very good job of that, particularly for older material.

Copyright lasts for so long, and distributors lose financial interest in works so fast, that they are often neither properly distributed nor available for anyone else to distribute.

Read more:

Australian copyright reform stuck in an infinite loop

In the book industry my research into almost 100,000 titles has found that publishers license older e-books to libraries on the same terms and for the same prices as newer ones. That includes “exploding” licences which force books to be deleted from collections even if nobody ever borrows them.

Publishers are interested in maximising their share of library collections budgets, not ensuring that a particular author continues to get paid or a particular title continues to get read.

As a result libraries often forgo buying older (but still culturally valuable) books even though they would have bought them if the publisher cared enough to make them available at a reasonable price.

Restricting access to books is not in the interests of authors or readers.

… and directing rewards where they are needed

If rights reverted after 25 years, as I have proposed and as Adams now proposes, authors would be able to do things like license their books directly to libraries in exchange for fair remuneration – say $1 per loan.

If authors weren’t interested in reclaiming their rights, they could automatically default to a “cultural steward” that would use the proceeds to directly support new creators via prizes, fellowships and grants – much like Victor Hugo envisaged with his idea of a “paid public domain” back in 1878.

We could do it all without changing the total copyright term imposed on us by the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement and other treaties. We could get creators paid more fairly while keeping Australian culture alive.

Reversion is the key.![]()

Rebecca Giblin, ARC Future Fellow; Associate Professor, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy? Caught in a landslide, no escape from reality. Open your eyes, look up to the skies and see… Some really awesome stories.

This month’s It’s Lit with Lindsay Ellis covers the much-maligned genre of fantasy.

Fantasy is a lens to explore what we as a society find important to our pasts, our presents, and future. Fantasy and science fiction often fall under the umbrella of “speculative fiction” – as a result they are often grouped together, especially in bookstores. But science fiction is a forward-looking genre propelled by the possibilities of technology (and the things that worry us about it), fantasy is … more backward looking.

Vote on your favorite book here: https://to.pbs.org/2Jes2X5

From Jack Milgram at Custom Writing.

Roger Beaty, Harvard University

Creativity is often defined as the ability to come up with new and useful ideas. Like intelligence, it can be considered a trait that everyone – not just creative “geniuses” like Picasso and Steve Jobs – possesses in some capacity.

It’s not just your ability to draw a picture or design a product. We all need to think creatively in our daily lives, whether it’s figuring out how to make dinner using leftovers or fashioning a Halloween costume out of clothes in your closet. Creative tasks range from what researchers call “little-c” creativity – making a website, crafting a birthday present or coming up with a funny joke – to “Big-C” creativity: writing a speech, composing a poem or designing a scientific experiment.

Psychology and neuroscience researchers have started to identify thinking processes and brain regions involved with creativity. Recent evidence suggests that creativity involves a complex interplay between spontaneous and controlled thinking – the ability to both spontaneously brainstorm ideas and deliberately evaluate them to determine whether they’ll actually work.

Despite this progress, the answer to one question has remained particularly elusive: What makes some people more creative than others?

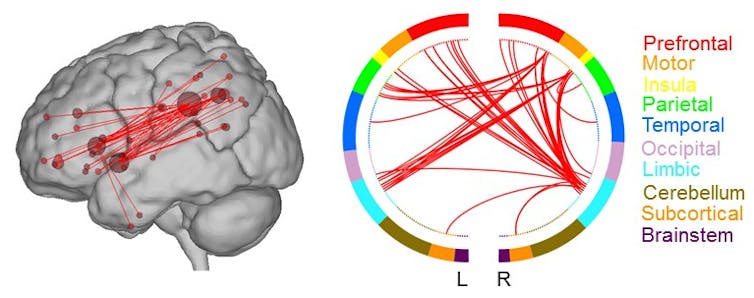

In a new study, my colleagues and I examined whether a person’s creative thinking ability can be explained, in part, by a connection between three brain networks.

Mapping the brain during creative thinking

In the study, we had 163 participants complete a classic test of “divergent thinking” called the alternate uses task, which asks people to think of new and unusual uses for objects. As they completed the test, they underwent fMRI scans, which measures blood flow to parts of the brain.

The task assesses people’s ability to diverge from the common uses of an object. For example, in the study, we showed participants different objects on a screen, such as a gum wrapper or a sock, and asked to come up with creative ways to use them. Some ideas were more creative than others. For the sock, one participant suggested using it to warm your feet – the common use for a sock – while another participant suggested using it as a water filtration system.

Importantly, we found that people who did better on this task also tended to report having more creative hobbies and achievements, which is consistent with previous studies showing that the task measures general creative thinking ability.

After participants completed these creative thinking tasks in the fMRI, we measured functional connectivity between all brain regions – how much activity in one region correlated with activity in another region.

We also ranked their ideas for originality: Common uses received lower scores (using a sock to warm your feet), while uncommon uses received higher scores (using a sock as a water filtration system).

Then we correlated each person’s creativity score with all possible brain connections (approximately 35,000), and removed connections that, according to our analysis, didn’t correlate with creativity scores. The remaining connections constituted a “high-creative” network, a set of connections highly relevant to generating original ideas.

Author provided

Having defined the network, we wanted to see if someone with stronger connections in this high-creative network would score well on the tasks. So we measured the strength of a person’s connections in this network, and then used predictive modelling to test whether we could estimate a person’s creativity score.

The models revealed a significant correlation between the predicted and observed creativity scores. In other words, we could estimate how creative a person’s ideas would be based on the strength of their connections in this network.

We further tested whether we could predict creative thinking ability in three new samples of participants whose brain data were not used in building the network model. Across all samples, we found that we could predict – albeit modestly – a person’s creative ability based on the strength of their connections in this same network.

Overall, people with stronger connections came up with better ideas.

What’s happening in a ‘high-creative’ network

We found that the brain regions within the “high-creative” network belonged to three specific brain systems: the default, salience and executive networks.

The default network is a set of brain regions that activate when people are engaged in spontaneous thinking, such as mind-wandering, daydreaming and imagining. This network may play a key role in idea generation or brainstorming – thinking of several possible solutions to a problem.

The executive control network is a set of regions that activate when people need to focus or control their thought processes. This network may play a key role in idea evaluation or determining whether brainstormed ideas will actually work and modifying them to fit the creative goal.

The salience network is a set of regions that act as a switching mechanism between the default and executive networks. This network may play a key role in alternating between idea generation and idea evaluation.

An interesting feature of these three networks is that they typically don’t get activated at the same time. For example, when the executive network is activated, the default network is usually deactivated. Our results suggest that creative people are better able to co-activate brain networks that usually work separately.

Our findings indicate that the creative brain is “wired” differently and that creative people are better able to engage brain systems that don’t typically work together. Interestingly, the results are consistent with recent fMRI studies of professional artists, including jazz musicians improvising melodies, poets writing new lines of poetry and visual artists sketching ideas for a book cover.

Future research is needed to determine whether these networks are malleable or relatively fixed. For example, does taking drawing classes lead to greater connectivity within these brain networks? Is it possible to boost general creative thinking ability by modifying network connections?

![]() For now, these questions remain unanswered. As researchers, we just need to engage our own creative networks to figure out how to answer them.

For now, these questions remain unanswered. As researchers, we just need to engage our own creative networks to figure out how to answer them.

Roger Beaty, Postdoctoral Fellow in Cognitive Neuroscience, Harvard University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Next generation comedy is here.

Source: Botnik Studios

I think it is safe to say that author careers are safe from being replaced by AIs for a few years yet.

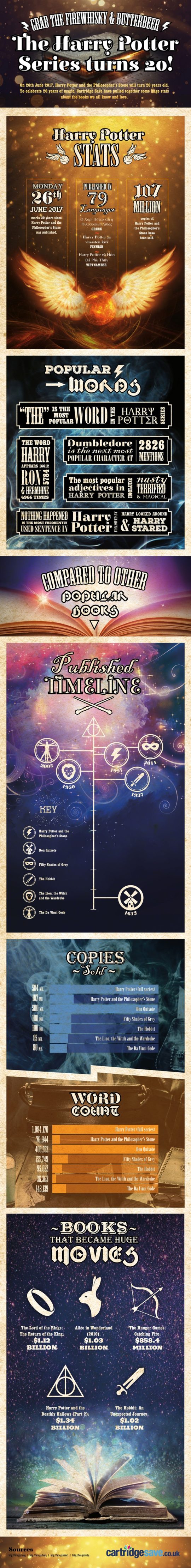

Did you realise the first Harry Potter novel was released 20 years ago? Did you feel really old just now?

Check out this really cool Infographic on the series, and revisit the differences between the books and the movies: Sorcerer’s Chamber of Azkaban, Goblet of Fire and Order of the Phoenix , Half-Blood Prince and Deathly Hallows.

Via Cartridge Save.

Harry Potter image from http://www.shutterstock.com

Di Dickenson, Western Sydney University

It’s 20 years on June 26 since the publication of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the first in the seven-book series. The Philosopher’s Stone has sold more than 450 million copies and been translated into 79 languages; the series has inspired a movie franchise, a dedicated fan website, and spinoff stories.

I recall the long periods of frustration and excited anticipation as my son and I waited for each new instalment of the series. This experience of waiting is one we share with other fans who read it progressively across the ten years between the publication of the first and last Potter novel. It is not an experience contemporary readers can recreate.

The Harry Potter series has been celebrated for encouraging children to read, condemned as a commercial rather than a literary success and had its status as literature challenged. Rowling’s writing was described as “basic”, “awkward”, “clumsy” and “flat”. A Guardian article in 2007, just prior to the release of the final book in the series, was particularly scathing, calling her style “toxic”.

My own focus is on the pleasure of reading. I’m more interested in the enjoyment children experience reading Harry Potter, including the appeal of the stories. What was it about the story that engaged so many?

Before the books were a commercial success and highly marketed, children learnt about them from their peers. A community of Harry Potter readers and fans developed and grew as it became a commercial success. Like other fans, children gained cultural capital from the depth of their knowledge of the series.

My own son, on the autism spectrum, adored Harry Potter. He had me read each book in the series in order again (and again) while we waited for the next book to be released. And once we finished the new book, we would start the series again from the beginning. I knew those early books really well.

‘Toxic’ writing?

Assessing the series’ literary merit is not straightforward. In the context of concern about falling literacy rates, the Harry Potter series was initially widely celebrated for encouraging children – especially boys – to read. The books, particularly the early ones, won numerous awards and honours, including the Nestlé Smarties Book Prize three years in a row, and were shortlisted for the prestigious Carnegie Medal in 1998.

Alan Edwardes/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

Criticism of the literary merit of the books, both scholarly and popular, appeared to coincide with the growing commercial and popular success of the series. Rowling was criticised for overuse of capital letters and exclamation marks, her use of speech or dialogue tags (which identify who is speaking) and her use of adverbs to provide specific information (for example, “said the boy miserably”).

The criticism was particularly prolific around the UK’s first conference on Harry Potter held at the prestigious University of St Andrews, Scotland in 2012. The focus of commentary seemed to be on the conference’s positioning of Harry Potter as a work of “literature” worthy of scholarly attention. As one article said of J.K. Rowling, she “may be a great storyteller, but she’s no Shakespeare”.

Even the most scathing of reviews of Rowling’s writing generally compliment her storytelling ability. This is often used to account for the popularity of the series, particularly with children. However, this has then been presented as further proof of Rowling’s failings as an author. It is as though the capacity to tell a compelling story can be completely divorced from the way a story is told.

Warner Brothers

Writing for kids

The assessment of the literary merits of a text is highly subjective. Children’s literature in particular may fare badly when assessed using adult measures of quality and according to adult tastes. Many children’s books, including picture books, pop-up books, flap books and multimedia texts are not amenable to conventional forms of literary analysis.

Books for younger children may seem simple and conventional when judged against adult standards. The use of speech tags in younger children’s books, for example, is frequently used to clarify who is talking for less experienced readers. The literary value of a children’s book is often closely tied to adults’ perception of a book’s educational value rather than the pleasure children may gain from reading or engaging with the book. For example, Rowling’s writing was criticised for not “stretching children” or teaching children “anything new about words”.

Many of the criticisms of Rowling’s writing are similar to those levelled at another popular children’s author, Enid Blyton. Like Rowling, Blyton’s writing has described by one commentator as “poison” for its “limited vocabulary”, “colourless” and “undemanding language”. Although children are overwhelmingly encouraged to read, it would appear that many adults view with suspicion books that are too popular with children.

There have been many defences of the literary merits of Harry Potter which extend beyond mere analysis of Rowling’s prose. The sheer volume of scholarly work that has been produced on the series and continues to be produced, even ten years after publication of the final book, attests to the richness and depth of the series.

![]() A focus on children’s reading pleasure rather than on literary merit shifts the focus of research to a different set of questions. I will not pretend to know why Harry Potter appealed so strongly to my son but I suspect its familiarity, predictability and repetition were factors. These qualities are unlikely to score high by adult standards of literary merit but are a feature of children’s series fiction.

A focus on children’s reading pleasure rather than on literary merit shifts the focus of research to a different set of questions. I will not pretend to know why Harry Potter appealed so strongly to my son but I suspect its familiarity, predictability and repetition were factors. These qualities are unlikely to score high by adult standards of literary merit but are a feature of children’s series fiction.

Di Dickenson, Director of Academic Program BA, School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

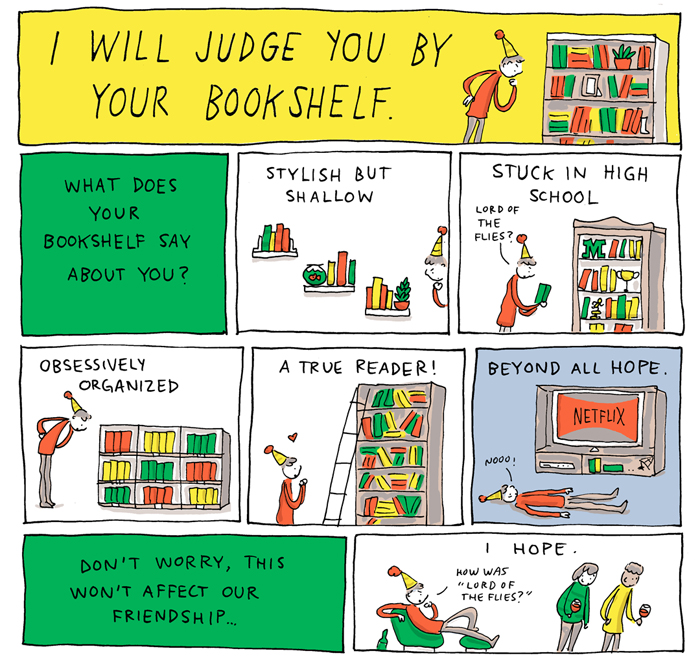

If you haven’t seen them already, these cartoons from John Atkinson at Wrong Hands are awesome. Go see his blog.

An artist by the name of Sebastian Errazuriz makes, among other things, functional sculptures. And what could be more functional than a bookshelf?

He turns dead tree branches into bookshelves for ultimate in dead trees holding up dead trees.

Original: http://www.boredpanda.com/tree-shelf-creative-bookshelves-bilbao-sebastian-errazuriz/

There are so many cool bookshelves around – yes, cool still applies to books. Here are 20 cool designs that will keep your books safe, albeit only a few as the shelves themselves are the centrepiece, not the books. I mean, who needs a bookshelf to actually store books? The Tardis and Tree bookshelves are my favourites.

Original: http://www.boredpanda.com/creative-bookshelves-bookcases/

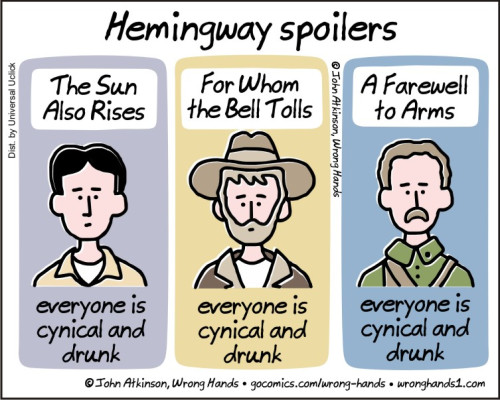

Recently I reposted a cool infographic about science fiction weapons, which was a continuation of my posts of infographics with cool comparisons (such as the fastest space ships). Bryan at EVELO liked those posts and sent me a link to his post on the Fastest Bikes in Fiction. Check it out.

Speeder Bike is still the coolest.

Graphic graciously stolen from Futurism.

I have no argument that these 5 authors are definitely some of the most influential science fiction authors of all time. You could also argue that they would also rank highly in their influence on fiction in general.

When I was younger Jules Verne was an author I devoured. He and HG Wells were well ahead of their time and are still influencing fiction now (see my comments here). While I have read Asimov and Clarke, I can’t claim to be a fan of their writings. Lots of great ideas, but the books I have read fell for the hard sci-fi trap of reading like physics text books rather than entertaining stories. I feel a little remiss in not having read any Bradbury as yet, at least none that I remember – my book reading before Goodreads is a bit of a blur.

What do you think of the list?

One of my favourite science blogs, From Quarks to Quasars, had a great post from Isabelle Turner that I needed to share. Take a look at the things from science fiction that became science fact, and wonder whether it was prediction, influence, or just wishful interpretation on our part.

This is the third* video in the CineFix series of Book vs. Movie differences. Well worth a watch.

* Yes, I’m skipping the second video because I haven’t read The Walking Dead comics and gave up on the TV show after spending half-a-boring season on that f@#$ing farm.

Did you know the Rambo franchise started with a novel about a man bringing the war back home with him? Let’s watch What’s the Difference and Lost in Adaptation.

David Morell’s career was really kicked off with Stallone wanting to make his first book into a movie. It wasn’t just that the franchise allowed him to become a full-time author, it was that he’d been rather savvy in retaining a few of the rights to the character and spinoffs.

Essentially, despite the fact that very little of his character remains in the sequels, Morell wrote the novelisations of the films, keeping his piece of the franchise $$. He has said that those sorts of IP negotiations can make a huge difference to a writer’s career.

Having read several of Morell’s books, I think most thriller fans would enjoy his work. And if you like the entire third act of a film being a buff guy shooting a large calibre machine gun at people, you’ll probably enjoy the Rambo films.

Normally I don’t talk politics. It really hurts my head when I repeatedly bash it against the desk when listening to politicians speak. Being apolitical I see little point in discussing what a bunch of self-serving failed lawyers do on a daily basis. Regardless, I’ve reblogged this post from uknowispeaksense – a fellow science nerd – as he has done a very good breakdown of both the houses of Australian parliament and where they stand on climate change.

Being a scientist, I find the current political inaction on climate change to be unacceptable. I find the denial of climate science to be akin to disputing gravity. Then again, I’m sure we could find politicians that would argue pigs can fly if there were enough votes in it. The science is settled. So I think it is important that people know where their politicians stand on what is quite possibly the most important issue to face humanity.

Also, this link has position statements of various parties.

Note: Senators’ positions here.

In September this year, 2013, Australians will head to the polls to exercise their democratic right and vote in the federal election, with each eligible voter hoping the party of their choice wins enough seats to govern for the next 3 years. Recently, Australian politics has seemingly become much like American politics with the right shifting to the extreme right and what were formerly centre left shifting slightly to the centre. In the process, the issue of climate change has become highly politicised. The idea of this page, is to highlight where each party and some selected individuals stand on climate change. In particular, I am interested in whether they accept the science or not.

Recent climate change is real, it is happening now, it is caused by humans and it is serious. This is not up for debate because the science is settled. Every major national scientific body in the developed world and the tens of thousands of scientists researching the climate accept this as fact. In my opinion, and many others, it is hands down the most important global issue and challenge facing humanity, and urgent action is required…now.

In order for global initiatives to be implemented to tackle the threat of climate change we must have governments who are prepared to act, and that means we must first have governments that accept the science. So how does our current crop of politicians stack up? To find out, Hansard, party websites, individual websites, press releases, newspaper, radio and television interview transcripts were searched for definitive statements made by our politicians that demonstrate that they either accept the science or not. Where a definitive statement wasn’t apparent, but the Member had mentioned some aspects of climate change, I emailed the Member requesting clarification of their position. Where no response was provided, the Member was classified as “no data” or “insufficient data”. Two Members made no mention of “climate change” or “global warming” at all in the places searched. They have been placed in the denier category. Retiring politicians (as at February 16, 2013) have been excluded.

An example of a definitive statement accepting the science on climate change is this one from Steve Irons, the Liberal Party Member for Swan, who when rising to speak in parliament on the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme Bill 2009 and associated Bills (CPRS2009), said…

“I accept the premise that climate change exists and that greenhouse gas emissions are contributing to the accelerated rate of climate change. There is evidence to support this and I lend my weight to those arguments.”

The link for that speech is here. An example of a definitive statement or statements rejecting the science is this barrage from Warren Truss, the National Party Member for Wide Bay as reported in the Australian newspaper.

”It’s too simplistic to link a finite spell to climate change.”

”These comments tend to be made on hot days rather than cold days.

”I’m told it’s minus one in Mt Wellington at the present time in Tasmania.

”Hobart’s expecting a maximum of 16.

”Australia’s climate, it’s changing, it’s changeable. We have hot times, we have cold times…

”The reality is that it’s utterly simplistic to suggest that we have these fires because of climate change.”

This is the usual grab bag of inane throw away lines, or variations of, one can find on any climate denial website. So, just how many of our politicians accept or reject the science of climate change?

Position on the science of climate change of current Australian members of the House of Representatives. n=150

What is clear from this graph is that the majority of Members accept the scientific consensus on climate change and have made definitive statements to that effect. When we break it down into party affiliations v position, we get an interesting look into the politicisation of the issue.

Position on the science of climate change of Members of the House of Representatives by political party affiliation. n=144 (6 retiring)

The striking thing about this graph that should be immediately apparent, is the fact that nearly every Australian Labor Party Member has made a definitive statement accepting the science of climate change. For the conservatives, the split is nearly 50/50. This can be broken down further…

Position on the science of climate change of Coalition Members of the House of Representatives by political party affiliation n=59

No real surprises here that the Nationals, being the representatives for large areas of “the bush” are climate change deniers. Their constituents tend to be highly conservative. Please note: retiring members and those for which there is no data have been excluded from this graph.

So, who accepts the science and who doesn’t? What is clear is that if you are of the right, there’s a good chance you are in the wrong. Here is a complete breakdown of the results with each member and their position.

Current sitting Members of the House of Representatives and their position on climate change science.

It’s probably fitting that the leader of the opposition, with a bit of help from alphabetisation, tops the list of deniers. This is the man who wants to lead the country and he refuses to accept the science of climate change. Remember, it is Abbott who claimed that “climate change is crap.” Now I’m sure there are supporters of Mr Abbott who will find quotes about his direct action plan to tackle climate change and hold this up as evidence that he is serious about the climate however, this is the man who will say anything for political expediency.

The thing that really bugs me about the list of deniers, is the presence of those National Party Members. While it isn’t surprising, these 8 people are supposed to represent Australian rural communities and have their best interests at heart. Climate change is likely to have very severe impacts on agricultural production in Australia. The CSIRO State of the Climate 2012 report states…

Australian average temperatures are projected to rise by 0.6 to 1.5 °C by 2030 when compared with the climate of 1980 to 1999. The warming is projected to be in the range of 1.0 to 5.0 °C by 2070 if global greenhouse gas emissions are within the range of projected future emission scenarios considered by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. These changes will be felt through an increase in the number of hot days and warm nights, and a decline in cool days and cold nights.

Climate models suggest long-term drying over southern areas during winter and over southern and eastern areas during spring. This will be superimposed on large natural variability, so wet years are likely to become less frequent and dry years more frequent. Droughts are expected to become more frequent in southern Australia; however, periods of heavy rainfall are still likely to occur.

These changes will require mitigation and adaptation activities to be undertaken not just by the agricultural producers, but also the communities in which they exist, and without government support, many will go to the wall. One wonders if a government full of climate change deniers will be able to make the important decisions that will secure Australia’s food future? For an insight into the potential challenges faced by agricultural producers in the future, as well as what will be required to adapt and mitigate, it is well worth reading the 2012 paper by Beverly Henry et al titled, Livestock production in a changing climate: adaptation and mitigation research in Australia. From the abstract…

Climate change presents a range of challenges for animal agriculture in Australia. Livestock production will be affected by changes in temperature and water availability through impacts on pasture and forage crop quantity and quality, feed-grain production and price, and disease and pest distributions. This paper provides an overview of these impacts and the broader effects on landscape functionality, with a focus on recent research on effects of increasing temperature, changing rainfall patterns, and increased climate variability on animal health, growth, and reproduction, including through heat stress, and potential adaptation strategies.

Full text available here. It’s not just livestock. It’s across the board. What will wine growers do in the face of earlier springs, increased risk of fungal diseases and changes in the microbiology and chemistry of winemaking? What will apple and stone fruit growers do to cope with a decrease in the efficacy of natural pest predators due to phenological changes in host species? Will wheat farmers be able to rely on a government full of climate change deniers to provide adequate R&D funding to combat lower yields? One need only look to Queensland to see what ideological climate change denial from a government looks like.

So, here are a few examples of the kinds of statements made by the deniers in our parliament. Remember, these people are ignoring the advice of tens of thousands of experts from around the world who are all saying the same thing, and they want to make decisions on your behalf, that won’t just affect you, but your children and grandchildren as well.

“The Prime Minister and her ministers have repeatedly declared that the “science is settled” and there is no need for further debate on how to respond to the environmental challenges from climate change. A Nobel Prize-winning scientist told me recently that “science is never settled” and that scientific assumptions and conclusions must always be challenged. This eminent Noble Laureate pointed that had he accepted the so-called “settled science”, he would not have undertaken his important research, which challenged orthodox scientific propositions and led to new discoveries, which resulted in a Nobel Prize.” Julie Bishop

That was Julie Bishop appealing to authority…the wrong authority.

“We are after all only talking about models and forecasts. Just as an aside, when the weather bureau cannot reliably tell me what the weather is going to be like tomorrow and then tells me that in 100 years there are going to be sea level rises of a metre as a result of climate change, I think I am entitled to exercise a level of caution in deciding whether to accept everything that is put to me about weather, climate and long-term trends.” Darren Chester

Darren Chester, failing to understand the difference between short-term weather forecasts and long-term climate trends. Scarily, he then goes on to discuss how wonderful it would be to dig out and burn all the brown coal in the Latrobe Valley. For the uninitiated, burning any coal is bad, but burning brown coal specifically is very bad. It burns much cooler than anthracite due to higher water content and less lithification and so you have to burn more of it to produce the same amount of energy.

“As I rise to speak on the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme Bill 2009 and related bills, I do so wondering whether the debate is being driven by alarmists or scientists. Are we debating this subject from a scientific standpoint or are we being caught up in the emotion of the times? We do live in an uncertain world and it is understandable why it can be easier to accept statements at face value rather than questioning what we are being told. I have been reading Professor Ian Plimer’s book on his response to the global warming debate. It makes for very interesting and illuminating reading, and I would recommend it to any member entering the debate on global warming.”Joanna Gash

Joanna Gash basing her uneducated and ill-informed opinion on the writings of a non-expert who has never published a single peer-reviewed paper on the subject of climate change and who is the director of seven mining companies. Can you say “vested interests” Joanna?

“To say that climate change is human induced is to overblow and overstate our role in the scheme of the universe quite completely over a long period of time. I note that the member for Fraser came in here today with a very strong view about how human beings have been the source of all change in the universe at all times. He has joined a long line of Labor backbenchers I have spoken about in this place before—amateur scientists, wannabe weather readers, people who want to read the weather, people who like to come in here and make the most grandiose predictions about all sorts of scientific matters without even a basic understanding of the periodic table, or the elements or where carbon might be placed on the periodic table. So the member for Fraser has joined this esteemed group of people who seem to be great authorities on science.” Alex Hawke

Alex Hawke, also confusing weather with climate but doing so in a spectacularly arrogant way. I love it. He’s not just saying, “I’m an idiot” but rather “I’m really an idiot and you better believe it! So there!” Who wants to ask Mr Hawke where carbon is on the periodic table? I know I do.

“As the only PhD qualified scientist in this parliament, I have watched with dismay as the local and international scientific communities and our elected leaders have taken a seemingly benign scientific theory and turned it into a regulatory monolith designed to solve an environmental misnomer. With a proper understanding of the science, I believe we would not even be entering into this carbon tax debate. To put it simply, the carbon tax, with all its regulatory machinations, is built on quicksand. Take away the dodgy science and the need for a carbon tax becomes void. I do not accept the premise of anthropogenic climate change, I do not accept that we are causing significant global warming and I reject the findings of the IPCC and its local scientific affiliates.” Dennis Jensen

Dennis Jensen, legend in his own lunchtime appealing to his own non-authority and single-handedly dismissing the honest, dispassionate work of tens of thousands of real scientists from around the world. At this point I should point out that Dennis Jensen does indeed have a Phd….in materials engineering on ceramics. Next time it starts raining cups and plates I’ll be sure to look him up. Oh, and he is also tied in with the Lavoisier Group and according to Wikipedia, boycotted parliament the day Kevin Rudd apologised to the Stolen Generation. I know that isn’t relevant to climate change but hey, if he’s a racist arsehole then everyone has the right to know about it. Anyway, I strongly urge my readers to check out the rest of his parliamentary rant. It is a cracker. Every single paragraph is filled with…well….crap. Who voted for this clown?

“Perhaps more concerning is the evidence that suggests climate scientists have engaged in manipulation of data, routine alienation of scientists who dispute the theory of anthropogenic global warming and the overall culture of climate change science that encourages group think and silences dissent.”Don Randall

Don Randall, reflecting on a newspaper article about “Climategate”no less. Obviously 9 independent investigations into “Climategate” all finding no wrong doing isn’t enough for the wilfully ignorant. For a good roundup of the whole saga, skepticalscience is the place to go.

These were just a few of the deniers and their ill-informed statements that I randomly selected. Having read through so many speeches and transcripts and media releases, I can attest that these are representative of the other deniers in the list. For me, the mind boggles when it comes to climate change denial. Presumably, these politicians are meant to be rational people. The appeals to the authority of non-experts really confuse me. It is akin to getting a plumber instead of an electrician to rewire your house. They wouldn’t get a vet to perform the brain surgery some of them clearly need. Why do they think the opinions of non-experts has any weight when it comes to climate science? It is completely irrational.

I guess it may seem to some that I am picking on the conservatives…and that would be correct, but I also have one or two big questions to ask of the ALP. If you all accept the science behind climate change as you claim and see fossil fuel combustion as the primary cause of recent climate change, why do you subsidise the fossil fuel industry to the tune of billions of dollars every year? Why not use that sort of money to develop the renewable energy sector and get us off our dependence on coal quicker?

This year’s election, if recent polling results carry through to September, is going to be won by the conservatives. Their leader, who admits to lying, who is on the record as holding different policy positions based on political expediency, is surrounded by men and women who are irrational in their non-acceptance of the science of climate change, many of them failing to grasp simple concepts such as the difference between weather and climate. Some of them suffer heavily from arrogance and one inparticular the Dunning-Kruger effect. A number of them have links to the mining industry and right-wing think tanks that are funded by mining companies and/or have mining executives on their boards. I wonder where their royalties loyalties lay? Is it with the people who have elected them, or their mining mates? I think I know the answer and it isn’t we the people. But then you’ve got the ALP subsiding the very industries they are claiming are the problem. Decisions decisions. For some, the decision might be about the lesser of two evils. Choose wisely.

Thanks to John Byatt for his valuable assistance with data collection.

If any politicians read this and feel they have been misrepresented, please feel free to contact me at unknowispeaksense@y7mail.com preferably with a definitive statement and I will make the necessary corrections and publish your response.

I have done the same thing for the Senate here.

Check out the National Party’s disconnect here.

Tyson Says: A point I should make about the results here, which was also made on The Drum last night: The Labor Party doesn’t allow for crossing the floor or dissenting public comment. Now, it isn’t like there aren’t penalties in the other parties for doing so, but this point needs to be considered when viewing the statistics.

Essentially, where it has all of Labor politicians on board with climate change, that is actually a party stance, not the individuals. I know from first hand discussions that there are Labor politicians who don’t believe in climate change science, but they won’t go on record as such because the party room has voted against them.

This is partly why we see such pathetic policies and hypocritical positions (e.g. mine coal like it is going out of fashion whilst claiming coal is to blame). Remember, politicians don’t care about science or facts, they care about making their supporters happy. Just don’t think that the voting public are their key supporters, because they certainly didn’t donate tens of millions to their party.

See why I’m apolitical?